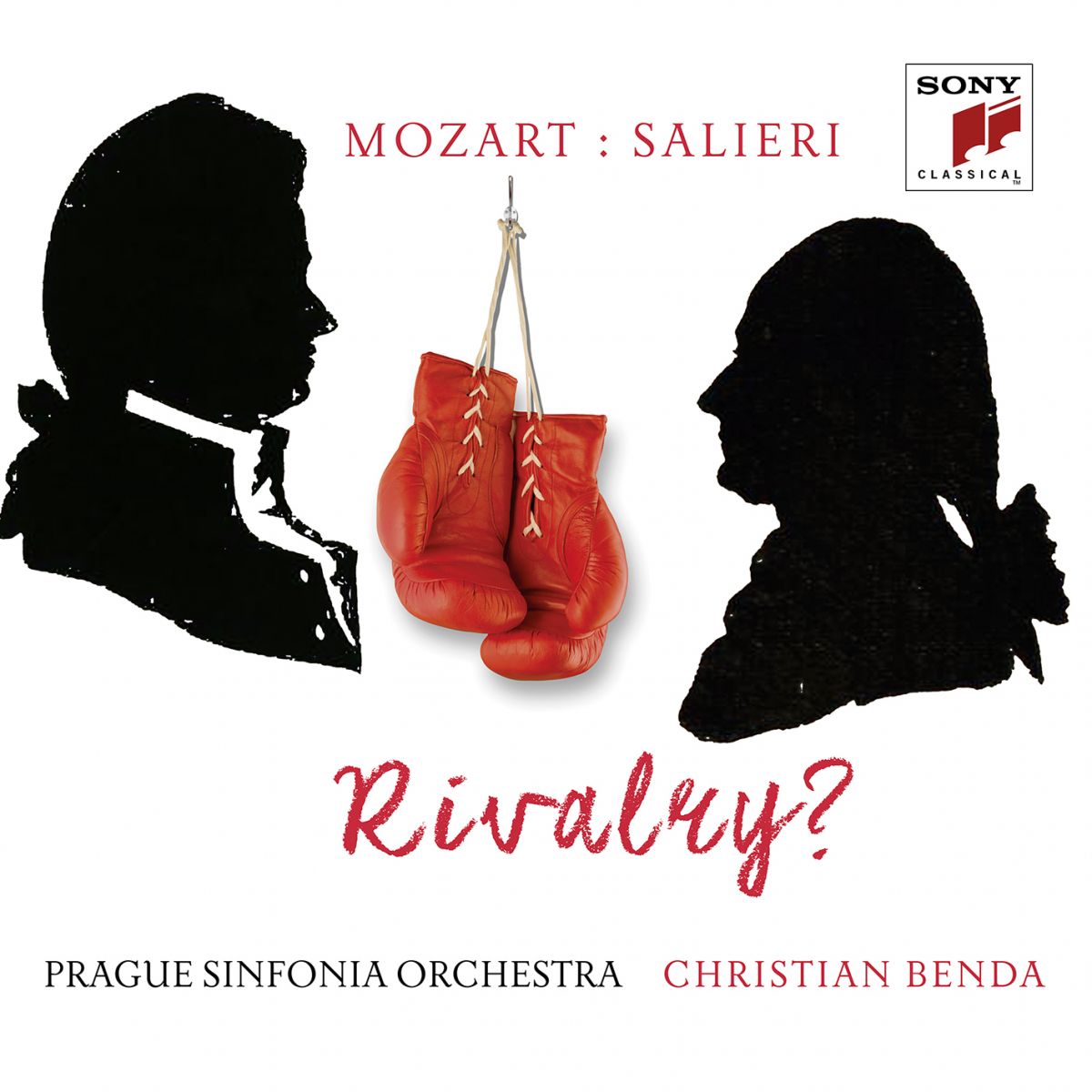

| NEW RELEASE Mozart versus Salieri: Rivalry? SONY CLASSICAL - 2 CDs Prague Sinfonia Orchestra/ Christian Benda |

|

SONY CLASSICAL - 2 CDs

Prague Sinfonia Orchestra/ Christian Benda

Release date: 05.04.2019

Labelcode 0190759195925

MOZART – SALIERI

The names Mozart and Salieri immediately bring to mind the romantic fiction which has dwelt on hearts and minds since Mozart's untimely death in 1791. Mozart was a free spirit, surrounded by a narrow-minded and spiritually-limited courtiers’ world; Mozart, the rebel against imperial authority, who was poisoned by a murderer as yet unrevealed; Mozart, whose body was tossed into an anonymous pauper’s grave, to cover up the traces of the crime. Salieri, on the other hand, who embodied every- thing the hot-headed Mozart detested, was the archetypical courtier, kowtowing to his superiors, dishing it out to his subordinates, scheming and envious, a mediocre composer so jealous of Mozart’s genius that he eventually poisoned him.

Although some of this may possibly be true, overall it is romantic fiction, which arose when old Salieri, delirious on his deathbed, accused himself of having murdered Mozart. This rumour circulated in Vienna: it can be found in Beethoven's Conversation Notebooks, where the latest “news” on the topic is mentioned. Salieri himself denied this statement. Tearfully he explained to his student, Ignaz Moscheles, “Mozart, – you know, I am supposed to have poisoned him. But no, it’s malice, nothing but malice. Tell the world, dear Moscheles, old Salieri, who is about to die, told you so himself.”

Recent research suggests other suspects – the Freemasons, for example.Mozart had shamelessly pressed his lodge brothers for loans, possibly seduced one or the other's wife during piano lessons, and, last but not least, made their secret rituals public in his Magic Flute. However, no valid evidence has yet been found.

The myth of Mozart’s poisoning by Salieri survives so persistently thanks also to many prominent advocates, including Alexander Pushkin. In his 1832 play Mozart and Salieri can be found all the motives still flourishing today: craftsmanship versus genius – Mozart, the unworthy vessel of divine inspira- tion, to whom everything comes without effort; and Salieri, who achieves nothing despite his hard work, and turns murderer out of “artistic envy”. The same constellation appears in Peter Shaffer’s 1979 play Amadeus, whose 1984 movie version by Milos Forman became one of the greatest film successes of the 1980s, winning eight Oscars.

The play and the film revived the myth of the poisoning, which had proved to be unfailingly effective. Possibly not quite so in the minds of the authors: as Pushkin's romantic concept is expressed to such a degree that one might suspect a hidden intent of parody or satire.

So what truth is there to this story? There must have been occasional jealousies between the established court music director Salieri and the newcomer Mozart, who as a freelance artist stirred up the Viennese scene. However, evidence of high mutual esteem is well documented: Salieri arranged numerous Mozart performances; he conducted the premiere of the Great G minor Symphony him- self. And Mozart reports enthusiastically in his last letter to his wife Constanze on 14th October 1791: “He listened and looked with all his attention, and from the overture to the last choir there was not a piece that didn’t elicit a ‘Bravo!’ or ‘Bello!’ out of him.” After Mozart’s death, his son became Salieri’s pupil.

The clearest evidence of a balanced relationship between Mozart and Salieri is a joint composi- tion: the cantata Per la ricuperata salute di Ofelia. In 1785, the Viennese music publisher Artaria announced its publication and mentioned a third composer: Cornetti; the name was in italics, in all likelihood a pseudonym. To this day, his identity remains unresolved. Various names have been put forward – even Emperor Joseph II in person. However, a lot speaks for the singer and composer Stephen Storace: his sister Nancy, one of the prima donnas of the time, to whom the work was ad- dressed, was equally esteemed by Mozart and Salieri, and had shortly before recovered from illness. The title of the piece refers to this: in the role of Ofelia in Salieri's opera La Grotta di Trofonio, Nancy Storace enjoyed triumphant successes after her recovery.

No copy of the 1785 print has been preserved – it is not even certain that the cantata was ever published; it was considered lost. In 2015, the composition reappeared in the Prague National Library collections, discovered by Timo Jouko Herrmann. However, this version differs from Artaria’s pre- viously announced cantata with piano accompaniment – an arrangement usual at the time for home performances. In fact, the Prague version contains only the soprano voice and a bass line typical of the orchestral scores of the period, so it could very well be some kind of “score shorthand”. For this first CD recording, the conductor Christian Benda has reconstructed the missing orchestral parts.

The occasional dissent between Mozart and Salieri was probably based on different stylistic schools: Mozart, born in Salzburg, was influenced by Italy, and in fact, in 1770, when he was fourteen, he received his first major opera commission from Milan; Salieri, on the other hand, was a French classicist, and was considered the heir to Gluck's reform of opera, causing a stir in this genre, even in Paris. Mozart is undoubtedly the more modern: through his existence as a freelance artist, and hence in his music, through the subjective appropriation of forms and means of expression. While Salieri had his successful career in the imperial capital Vienna, Mozart celebrated his greatest triumphs in Prague. The kingdom of Bohemia was ruled in personal union by the Emperor in Vienna, Prague was therefore not under the pressure of the mechanics of social and political control of an imperial capital. There was a spirit of opposition, more open to aesthetic innovation, and also stirrings of political unrest, with the constant desire for freedom and independence always alive. Nonetheless, the country had to wait until 1918 to become independent.

In 1938, the German and subsequently the Soviet occupation marked the end of independence; in 1968, the “Prague Spring” was immediately repressed; in 1989, after more years of oppression, came the “Velvet Revolution” and the fall of Communism. The leader of the Civil Rights Movement, playwright Václav Havel, a school-friend of Milos Forman, moved to Prague Castle as democratically elected president. Mozart's music accompanied this turning point in history: at Havel’s inauguration in 1990, the proclamation of general amnesty was celebrated with a performance of the Coronation Mass. A group of Prague musicians gathered in the hall of the main railway station after Havel’s death to perform Mozart’s Requiem in his honour. There is no doubt that Mozart's music still falls easily on ears in Prague to this day.

Ingo Dorfmüller, 2019 - translation: Deborah M. Lockwood & Ian Menzies

- MOZART VERSUS SALIERI: RIVALRY?

- SONY CLASSICAL - VINYL & CD

- ROSSINI - BLU-RAY High Definition

- SCHUBERT - Complete Overtures